Wine Meets Umami

When soil, snow, and cuisine converge, Pinot Noir takes on an unexpected identity

Japan has a way of overwhelming you. A few days feel like weeks: train stations thrum with precision, neon reflections pulse against the night, and meals arrive with flavours that force you to rethink everything you thought you knew about food. Travel here is a constant negotiation between disorientation and delight. My own journey began in Tokyo and stretched north, past small towns and slow-moving trains, until I reached Sapporo. It is a city alive with energy but, for me, tinged with fatigue. After two weeks of darting around like a wide-eyed child in a theme park, I felt more like a passenger than a traveller. And yet, even in that haze, one thought kept returning: could the same spirit that shapes Japanese cuisine also shape its wine?

For decades, Japanese wine producers looked abroad for inspiration. Bordeaux was the early model: structured reds with tannin and heft. Later, Burgundy crept in, with their ideas of finesse and fruit. But the essence of Japanese food has always been something different. Kaiseki meals, the height of culinary tradition, build flavour not by overpowering but by balancing. A broth enhanced with kombu, a piece of fish accented with a brush of soy, a wild mountain herb added for quiet harmony. The word that floats through all of it is umami.

Wine, of course, is not designed with umami in mind. Its language belongs to Western traditions: minerality, acidity, tannin, terroir. But what if terroir could mean more than soil and climate? What if it could include food culture itself?

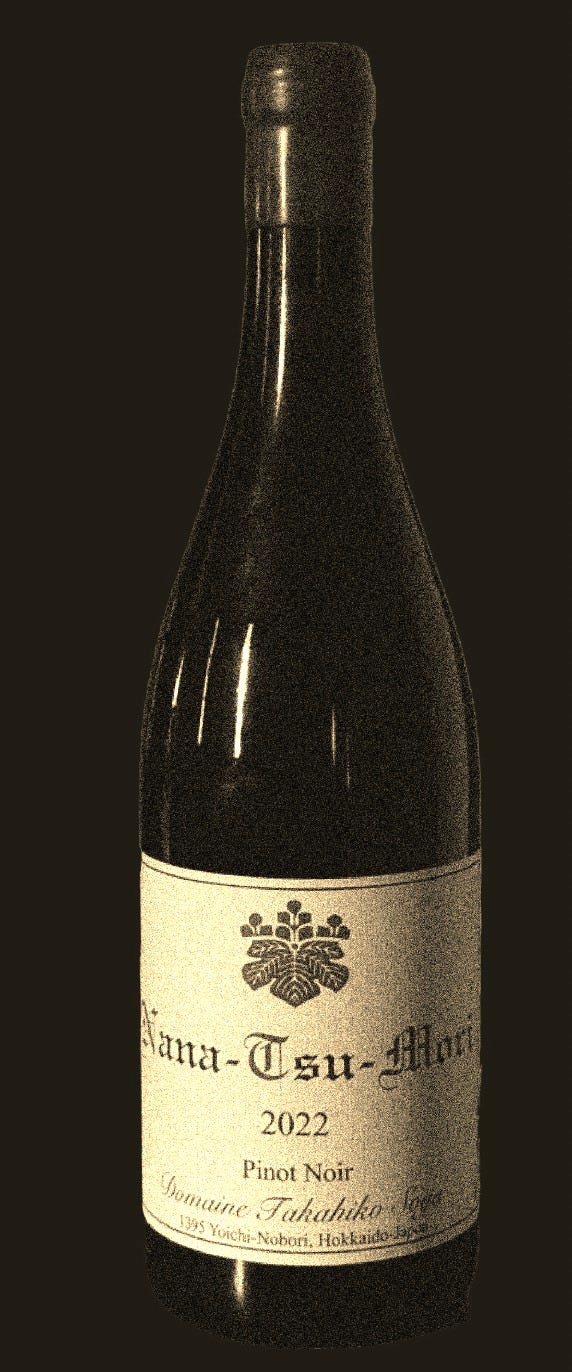

That question brought me north to Hokkaido, Japan’s frontier of wine. Here, in the coastal town of Yoichi, whispers circulate about a producer whose bottles have achieved unicorn status. Domaine Takahiko. The name appears on the wine lists of restaurants from Tokyo to Paris, yet the wines themselves are almost impossible to find. Sommeliers murmur about them as if they were flavours rather than liquids: dashi, mushroom, forest floor.

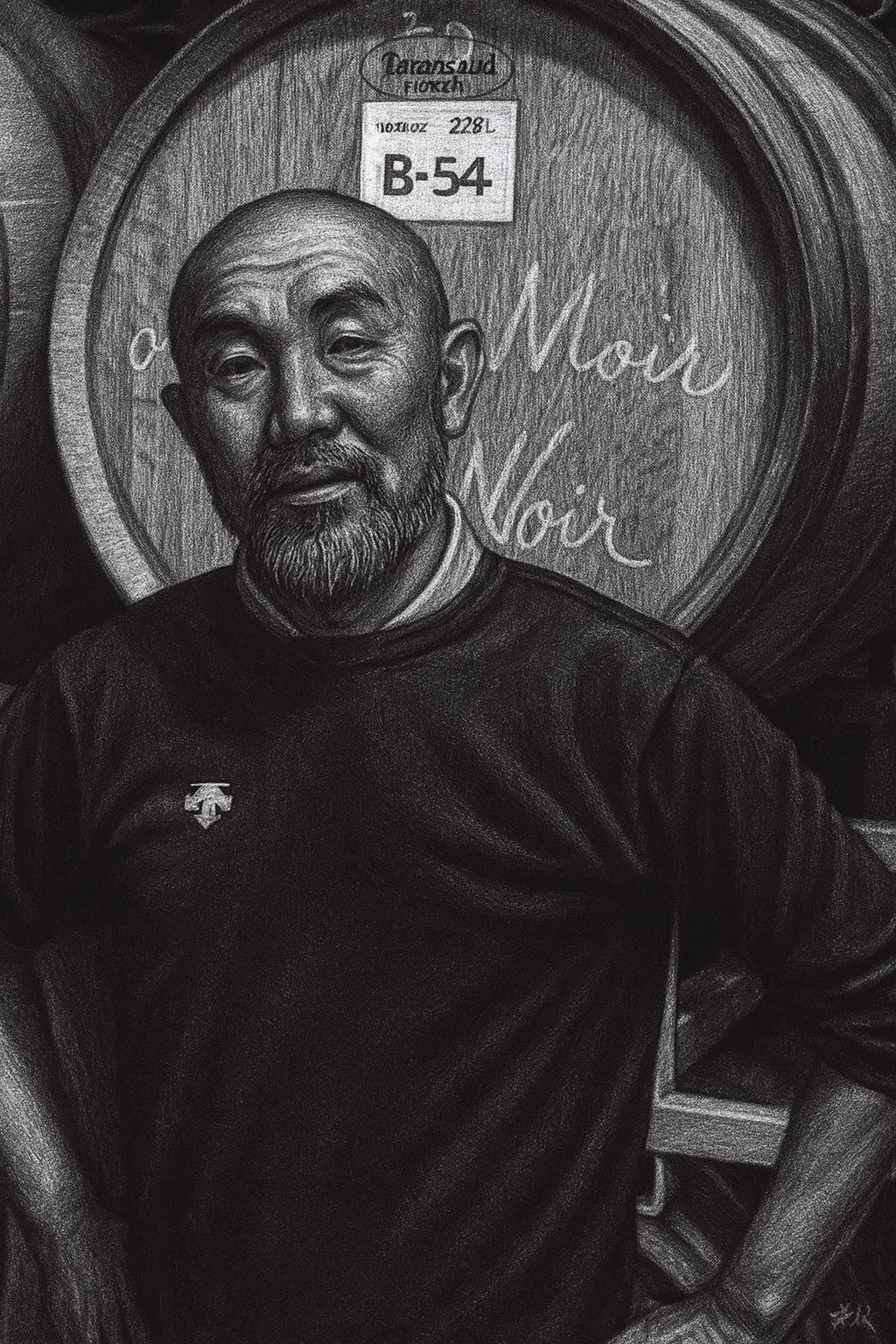

Reaching Yoichi means crossing landscapes that look, at first, nothing like the wine world’s capitals. Snow falls for months, blanketing vines in a protective layer that shields them from the deep cold. Here, a small group of producers is building a truly distinctive wine identity. And at the centre of it all stands Takahiko Soga, the man many credit with rewriting the script. His Pinot Noirs have become shorthand for a new approach: wines that do not just pair with Japanese cuisine, but seem to be born of it.

When people talk about Domaine Takahiko, they do not simply mention terroir in the French sense. They speak of umami. They describe wines that echo the same philosophy guiding chefs for centuries: let the natural character of the ingredient shine, support it with harmony, never mask or dominate. One wine writer compared the experience to a kaiseki meal: a series of notes that unfold gently, subtly, but with undeniable power. This philosophy has implications that reach far beyond Japan. It suggests that wine need not be locked into European paradigms, that terroir can mean culture as much as geology. It asks whether food and wine are truly separate at all, or whether, in places like Yoichi, they might converge into a single tradition.

Standing in the vineyards of Hokkaido, it is easy to see how radical this is. The Western canon has always prized certain qualities: structure, longevity, typicity. But in Japan, where humility and harmony are virtues, wine can take on another role. It can be a mirror of cuisine, a liquid that channels the same principles as a bowl of miso soup or a dish of mountain herbs.

The more I travelled, the more I realised that this was not just about one producer. It was about a shift taking place across the region. Apprentices who trained under Soga have planted their own vineyards. Small wineries have sprung up in Yoichi, each taking cues from the land, the snow, the food. What began as one man’s experiment is starting to look like a cultural movement. And yet, the essence of Domaine Takahiko remains elusive. Partly because the wines vanish the moment they are released. Partly because, like umami itself, they resist simple description. To say “Pinot Noir” is true, but inadequate. To speak of soil and snow explains something, but not everything.

Which leaves us with the same question that drew me to Japan in the first place: what happens when wine is shaped not only by earth and climate, but by cuisine and culture?

I set out to answer this question in a long piece drawn from my conversation with the winemaker himself. The full article appears in our magazine-book Mizanplas, which you can order here: https://www.mizanplas.com/mizanplas-english