Tasting Menu Trilogy: Part One by Alain Chapel

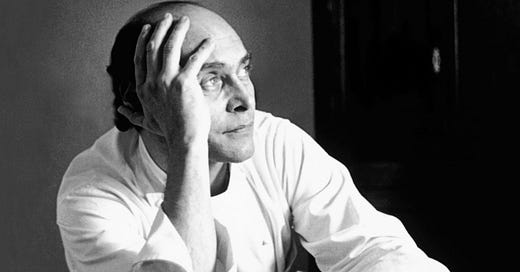

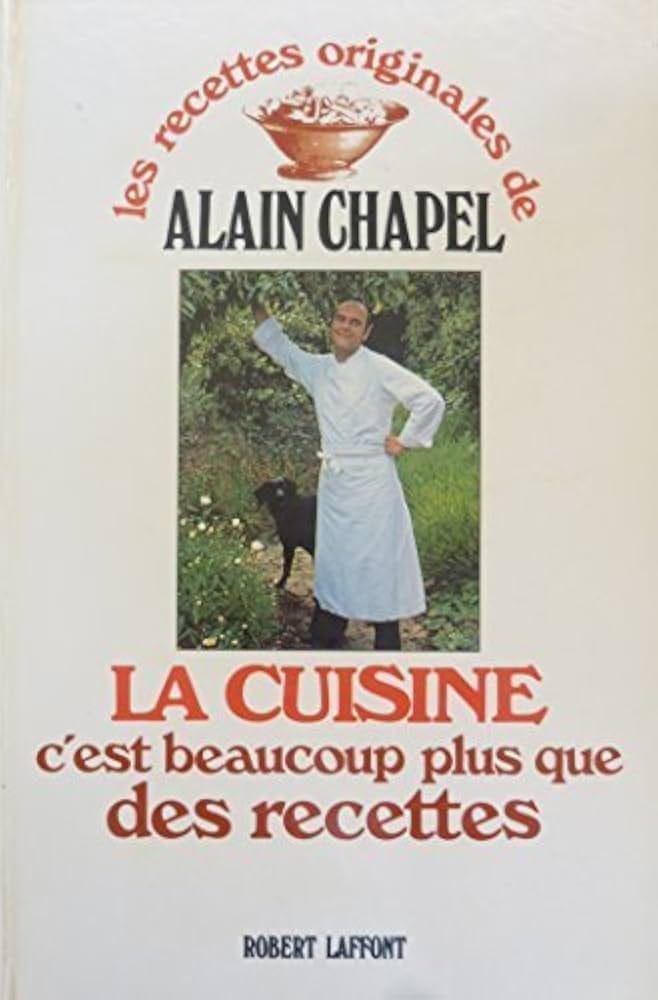

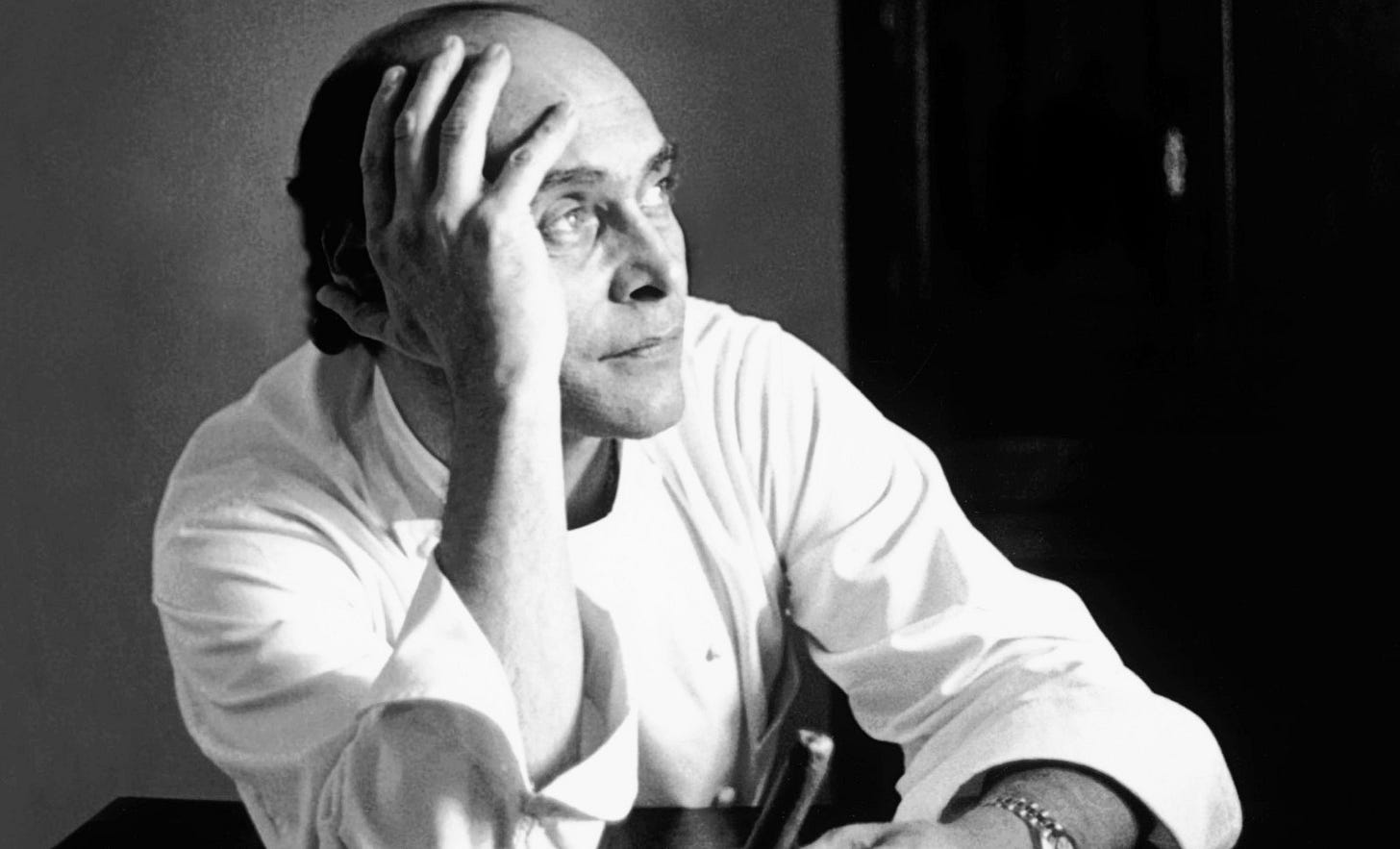

In 1980, the Parisien publisher Robert Laffont, in his series of cookbooks by the greatest chefs in France at the time, issued Alain Chapel’s La Cuisine c’est beaucoup plus que des recettes. Still today, the gastronomic world considers it one of the most consequential cookbooks of all time. One reason for this is the 50-page narrative Chapel wrote with the Lyonnais journalist Jean-François Abert. What comes across in this introduction is the wisdom and sensitivity of Alain Chapel and what made his restaurant in Mionnay, 18 km northeast of Lyon, one of the greatest restaurants in the world. I have translated the introduction, which we will share with you in segments over time. As we feel that his opinion about “Le menu-dégustation” rings true almost 45 years later, we offer it as the first part of our tasting menu trilogy that also includes David Kinch and Joerg Zipprick. Although Chapel expounded on this well before the dozen or two or three-course tasting menu came into being, the basic shortcomings he addressed hold true even more so today.

The fashion today is what we call the tasting menu: a long decline of dissimilar dishes, in capricious order, and whose nomenclature leaves much to be desired. This variety above all is meant to make a big impression that is reminiscent of service à la française in the 17th to 19th century, and which forced the diners to astonishing gymnastics of their taste buds. How can we constantly rekindle these changing flavors, these superficial and allusive dishes, and this strange game of passing them around like a rabbit in a top hat, and then becoming invisible as soon as they have been looked at?

For the customer dazzled by the show given all these flavors, it would therefore become a matter of knowing this or that restaurant kitchen from A to Z, the same as we would know the complete works of a great writer. The tasting menu would respond to this fantasy of exhausting all the possibilities of a restaurant all at once, as one would hope to exhaust the merits of a book by reading summaries or the condensed version and which has something in common with the supposedly gratifying value that today's tasting menu cuisine finds in the adjective short as with short portions, short cooking, short sauces, etc., with again, as an illusory root of the word, the verb ‘to run’ (court, courir). The tasting menu is thus short of cooking with short sauces.

However, it seems to us that to practice this way, the time for breaks between courses is not very well managed. Five or six dishes follow one another which do not resemble each other and which, pressed to the rhythm of the service, accumulate their diversity, pile up their differences, and add up their contradictions instead of browsing a restaurant menu with anticipation or intoxication specific to the menu. A tasting menu, however, may not be the best way to learn about a dish.

It's not so easy to compose a menu around two or three dishes and to give the appropriate role to wine, which aren't content to be clever extras. What then of the tasting menu, with its contorted flavors, multiple sauces, and unpredictable, if not bizarre, aromas? And it's all part of a fast-paced assault on the serious diner where, like at a rail crossing, “one dish can hide another.”

At Mionnay, although we don't have a tasting menu, we still offer a variety of taste, such as with the idleness of an aperitif with little dishes that have a flavor of patience: fried goujons, fried parsley, bouquets, pied-de-cheval oysters—all those slightly iodized tastes that click on the tongue before the meal and with which we propose a bottle of Pouilly-Fuissé or a white Bellet. The diner makes a kind of sensual contact with his meal and starts by using his hands. We'd like them to feel more reassured about their appetite, as we do with this first manifestation of what we hope is culinary intelligence.

The aperitif is therefore a time of trust. It's a time to establish a rapport, if possible a connivance. It's a time for diners to feel enveloped in comfort, to relax in a house that's no longer completely unfamiliar to them, and which they might otherwise have hesitated to order. But it can also be a way of making the diner feel at ease, dreaming about ordering. We can then have him well-served.